On a cold windy night, Daniel Buchbinder came down from his rooms and walked through the narrow streets along the riverfront until he arrived at the Stockyards Café. Inside, the owner, Frank Botto, a surly, bear-shaped man with one shrunken ear, greeted him with a rush of air from between his teeth. Despite his effort to conceal his agitation, Daniel’s hand shook when Botto handed him the menu, which he knew by heart but always accepted. He liked to have something on which to train his eyes while waiting for his order to be taken. It was late on a Sunday evening, and he was the only customer in the place.

As Botto turned away, Daniel said timidly, “I’ll need another menu,” moving his vision vertically up and down the page to pretend to study it and to avoid Botto’s glance. The café owner hung over him and snatched a menu off the table behind his, throwing the menu down opposite Daniel as if insulted Daniel would have an ally in the room while he had no one with whom to share his thoughts on this bitterly cold night.

These two saw each other nearly every night, for despite Botto’s inhospitality, he was an excellent cook. Besides his livelihood, Daniel was a bumbler at nearly everything and would starve in short order if he had to cook for himself. He was fortunate to live within walking distance of one who followed the command “Feed my sheep,” even if the café owner cared so little for the sheep themselves, particularly Daniel, who, being meek as a tear, drove him to distraction.

Botto both loathed Daniel’s presence and looked forward to it every night. He was never so pleased as when business was slow enough that he and Daniel were alone in the place and he had the leisure to stare daggers at the heart of the tired Jew while he ate, Daniel’s eyes averted yet restless. If asked why he detested this particular customer so, Botto would have felt hard pressed to find a reasonable answer and, in fact finding none except his own perverseness, would have answered with a sneer, working his fists, “Oh, Buchbinder, the little moth, he’s like no one else.” His hands would twitch sometimes with relish at the thought of tearing a delicate creature to bits for the sheer pleasure of knowing that the deed afforded him no challenge. He thought to himself, I could tear into Buchbinder as easily as into a package of crackers, and looking at the lean, stooping figure, felt such tenderness in his chest, knowing this was true, that he could have hugged Daniel to him to protect the Jew from his abuse. All these thoughts Botto kept to himself. He has no idea how close he is each and every night to utter decimation, and I spare him magnificently each and every time, only staring, staring.

Botto lumbered to the stove, emitting a disheartened grunt at every step, and stirred something in a pot. Daniel never ate in company and was utterly alone in the world as far as Botto could tell. He often passed Daniel’s shop and saw the Jew humped over his work table, sewing the pages of a book together with the thick linen thread, reminding him, for all his fierce concentration, of a tidy spider. Botto was loathe to admit how frequently he went that way for the sole purpose of spying on his secret concern, on his way to intercept his granddaughter after school or early in the morning on his way to buy his vegetables at the farmers’ market, a whole side of beef at the stockyards. He met the Jew, if only at a distance, on his way to nearly every place he went and found him to be always alone. Daniel’s isolation added further fuel to Botto’s hatred of him and made his delight in intimidating him all the more poignant, for he knew the Jew had no one to complain to.

But now, by indicating that he would await company, Daniel roused him to fury. Botto shook with contempt and a desire for revenge that Daniel could keep his secret from him in his own café, though Botto knew nearly nothing of his personal life as it was. For that matter, everything about the Jew was a secret kept from him. But this was the last straw. He dropped the spoon and, with his mouth stretched unusually taut, rounded the edge of the counter and moved like a seething steam engine toward the table. Meanwhile, Daniel had removed his parka and ear muffs and folded them neatly, almost lovingly, on an adjacent chair. Sensing Botto’s approach, he lowered his head over the menu once more, stroking the back of his neck with one hand, following a line of print with the other.

“Oh, Bejesus,” Botto said, pulling a chair out and sinking into it with a belch. He stared hard at Daniel, but his adversary would not look up from the menu. “I think most of us are barely getting by,” he went on, his voice probing for a nerve. “I think most of us in the business world are. You, for example, sewing words into leather bindings, and for what? Do you think anyone takes down those books once you’ve sewn them so prettily and looks into them? They’re for show. I’d stake my life—not a one of those books you’ve bound has ever been read. But then, so what? You must bind them and stamp them in gold leaf, tool the curious designs knowing it’s your work and not the words you bind that’s important. Even then, what does your work receive? A glance? A compliment? And then, the kiss of death: the bookshelf for which it was made, like the cushions are made for the couch. And you, you’re like those books you bind, that are crammed into a tight spot on the shelf—just as you are into that cramped workshop of yours—and forgotten, unappreciated. We become like our work.”

“If our work is a passion,” Daniel ventured. Daring to look up for a moment, he saw that despite the café owner’s supposedly sympathetic words, Botto’s eyes contained a hatred of him that Daniel struggled to fathom. Botto probably could not love those he must without hating those he needn’t hate. Daniel didn’t mind. He sensed that, on some level missed entirely because of the shaky footing of their relations, the café owner was a good man. “And then if it is a passion, it doesn’t matter where it puts us, in an overstuffed bookshelf or into the fire. We must work, Botto, and live, too, as if every breath were a privilege we haven’t the appreciation to grasp.” He looked furtively at his watch and then at the black window which rattled from a renewed assault by the wind. The reflection of the room tilted precariously as the plate of glass shook.

Botto jealously kept track of Daniel’s gaze. He was amazed at what spite he felt that the lonely Jew might have won a friend and was expecting him momentarily and, furthermore, that Daniel had divulged nothing of this friend’s identity. It was more than Botto could endure from one he hated so intimately.

“Yes,” Botto continued, “but at least you never had the burden of a family to support.” He lowered his dandruffed red eyebrows. “For whatever reasons—ill luck, fear, preference—you never married.”

He paused and rotated his chin to give Daniel time to select his reason from the choices offered. Slowly a bulge appeared in Botto’s left cheek and continued to grow until he had stretched the skin so far that in another moment his cheek would separate from the jaw bone. He uttered a sharp yowl and put his tongue back where it belonged, slapping the table top with his palm and lurching forward, his eyes bulging. “I say!”

“Are you all right?” Daniel asked, blinking rapidly, and even fearfully, as if he had just been told he and Botto would be spending all eternity together, tied to opposite ends of a short rope. He pictured Botto biting continually at his own end of the rope and commanding him to do so to his own. How could he patiently endure being told to do what he had known a millennium ago was fruitless? Botto was one of those who believed vividly that he would break his bonds in the next instant, contrary to years of

“Are you all right?” Daniel asked, blinking rapidly, and even fearfully, as if he had just been told he and Botto would be spending all eternity together, tied to opposite ends of a short rope. He pictured Botto biting continually at his own end of the rope and commanding him to do so to his own. How could he patiently endure being told to do what he had known a millennium ago was fruitless? Botto was one of those who believed vividly that he would break his bonds in the next instant, contrary to years of

evidence that the task was insurmountable, success only a dream. As such, Daniel gently considered him a fool. But the irony in that, he saw clearly enough, was that tonight he was acting out Botto’s belief, right under the other man’s nose. But do you have to ask pardon for scoring on another man’s belief, he asked himself, for walking cleanly through a wall the other man butts his head against? Daniel’s reluctance to offend compelled him to ask pardon for just about everything he did in the presence of God and Man, and he felt almost as if he owed Botto a tribute for acting in his own interests in the café owner’s domain.

The Stockyards Café was Daniel’s appointed place of meeting with the woman, Nalia Koberg-Franz, who had answered his ad in the paper. She had described herself as stout. “A stout Gentile. Do you mind?” “The ‘stout’ or the ‘Gentile’? ” he had written back. They both made something of a joke of it.

Before coming tonight, Daniel had made two false starts: returning to his rooms first for a shot of the whiskey one of his Christian customers had given him at Christmas, then for a swig of mouthwash (as he had described himself as a non-drinker). In one of her letters, Nalia had expressed pleasure in his abstinence. She said that she suffered from swollen kidneys and for her health’s sake could not afford to conviviate with those in whose daily routines liquor formed a part. Her letters were peppered with such overblown phrasings. Daniel took pleasure in repeating them to himself, much as if savoring the memory of a fine meal. Because of these indulgences in language, he pictured Nalia as someone who would fuss over him and make special efforts in cases where someone else would only make do.

For years Daniel had been planning to fall in love but had never quite succeeded. He watched lovers with envy and admired their situations. But for making their situations his own he felt an incapacity and even fear, lest he should prove incompetent, involving himself too far in a compromise from which it would later be difficult to withdraw as needed. Romance had long held a tyrannical attraction for him. It was like the forbidden fruit and might give him knowledge of things better left unknown: his inability to sustain love over a long run or to inspire it.

He felt he had somehow been tricked into placing an ad by that impassioned self that hid in other people’s lives. “This is not me,” he had said imploringly as he walked to the café tonight. And yet he kept walking. He prodded himself, saying, “You’re forty-three, Daniel. Soon you’ll be seventy-three. That’s thirty years you might be happy. There might be a new life for you, even at forty-three. Furthermore, Nalia Koberg-Franz might not consider you attractive. And unless you find this out, you’ll take all on yourself the blame for abandoning the project.” He consoled himself, reflecting that the meeting would be worth having if only to find out he did not appeal to her. A stout Gentile might not appeal to him either, although her letters enchanted him with their slightly clumsy footing. Their awkwardness brought to his mind a large woman’s walking for the first time on heels too small for her. He was charmed by the image and would not release it. He wouldn’t care that she had a figure like a bathtub as long as she had dainty lips and said “as I know of” every once in a while, as she wrote in her letters. The shape of things did not matter to him.

“Tonight,” he told himself, “I am going to do something I have put off for a long time. I am going to meet my love face to face, and perhaps this will help me solve the riddle of existence. Why do I bind books no one reads, if Botto is to be believed? Why does he feed us all out of his larder when he hates each and every one of us and to him we are only so many cattle on a long drive to the grave? He is a man soured on life but unable to resist preserving it in others, if for a profit. Why all these contradictions unless it is toward such a privilege as this, to meet the love I thought I’d never have?”

Botto narrowed his eyes suspiciously on him. The detestable Jew was having thoughts he couldn’t discern. What misery this was, to be himself, separate from everyone, particularly from those he hated. After all, those he loved would always be there, but the objects of his wrath, weren’t they liable to take off at any moment, never to return? The incompleteness of life shook him up. He must be getting old, although at fifty-two he shouldn’t be ready for the grave. He ought to have many ideas for living out his existence, although not one occurred to him except that of making the ugly Jew disclose how he had won a friend he had never mentioned.

“I have four sons, and they all stole stereo equipment at one time or another,” Botto said, hitting himself tenderly on the forehead with his fist. At that moment he longed to change places with Daniel, to be waiting in someone else’s café for a mysterious stranger to appear and listening to another man’s lament about his wayward sons. He actually convinced himself, thinking of his own circumstances, that Daniel’s life was one of luxury and ease. “It’s this neighborhood,” Botto said, looking around himself defiantly and flaring his nostrils as if the neighborhood were closing in on him. He turned his head aside and made a spitting sound, painfully aware that while he envied Daniel, Daniel was content within himself and did not envy him his life. He shook his head slowly. “And to have grandchildren who laugh at you behind your back and call you ‘Stinker’ and ‘Fatty’ and ‘Dishtowel.’” He spread his arms. “The whole world began here, for them. This is their origin, their genesis. And they’re all too good for it, too good to come in and help. They all want to go to the finest restaurants with the highest prices. They think their butts don’t stink anymore, that mine does all the stinking for them. I swear it doesn’t.”

He longed bitterly, then, for Daniel to confide in him, but all the Jew did was look steadily at him with his gentle dark eyes. The constant wetness of those eyes robbed their owner of every semblance of manliness. Botto imagined that one hard slap on the face would dry them up for good.

“What is the most beautiful line you’ve ever read?” Botto asked suddenly. “I mean for you to tell me!” he blared, and then his voice lapsed back into the uncustomary gentleness it had assumed before. “You’ve bound many, many books, and you must have browsed a great number of them, I am sure. Surely a line once leapt out at you and has stayed with you ever since. All those books?” he said, shivering. “I can’t imagine it. How horrible. But, tell me.”

Botto leaned his hulking torso over the table and folded his hands close to Daniel, who sat with his rib cage pressed against the table’s edge. Botto’s earnestness touched him. A change had come over the caféowner. Daniel had known him for seven years and had never seen him eager to subject himself to the written word. Yet it seemed he hung on that hope now. Perhaps he was looking for something conciliatory to say to the children who shunned him, or something tender to say to his wife, to make her recall her first feelings for him. Perhaps his perpetual irritability was due to the fact that for years running he had had no faith in the word, written or spoken, and this appeal was a last-ditch effort to work out his salvation. Daniel wished he had never come here tonight, for Botto seemed to read a great deal of significance into his presence, and his attempts to have a normal

conversation made the owner look even more crazy than he did when he only muttered to himself and glared and hit his forearm with the dishtowel. One of the horrible things that Daniel had observed about going out into the world was that he never knew whether people were going to appropriate him for good or evil. He felt unprepared to accommodate either force but preferred to work steadily, alone.

conversation made the owner look even more crazy than he did when he only muttered to himself and glared and hit his forearm with the dishtowel. One of the horrible things that Daniel had observed about going out into the world was that he never knew whether people were going to appropriate him for good or evil. He felt unprepared to accommodate either force but preferred to work steadily, alone.

“The most beautiful line I can remember?” Daniel said, feeling trapped. For someone who until this moment had treated him with spite, Botto was asking a lot of him. The bookbinder’s attention roamed over the entire room: first to the clock, which showed a quarter after eight—meaning that Nalia was already fifteen minutes late—then to the white stove with the red knobs (on which three rings of fire burned uncovered and the kettle of soup boiled away over the fourth burner), to the brass coffee urn, and on to Botto’s waiting boil-covered face, through which shone a light of childish anticipation. It nearly broke Daniel’s heart to see that childish gleam pressed through a face so ugly and unaware of its ugliness. How could anyone hate, that was what he wanted to know, when the one who had it in for you could be so unexpectedly child-like? There didn’t seem to be a way to harden his thoughts up to a pitch for self-preservation. He was too quick to glimpse some gesture of his would-be enemy’s that seemed to harken back to a time before their differences put them at odds. Finally, he laid his gaze against the glass door and each of the shivering windows. “I’m looking so forward to meeting you face to face,” Nalia had written, “to see the author of such beautiful sentiments.” Words like those were cruel as any taunt if the one writing didn’t live up to them.

“You’ll laugh,” Daniel said, trying hard to forget his own concerns for the time being and to concentrate on Botto, who honestly appeared to be seeking consolation from him. Instead of making him feel important or vengeful, the responsibility depressed Daniel.

“No, I won’t!” Botto said.

“But it’s a line of poetry.”

“Poetry is fine.” Botto spread his arms enthusiastically. “I’ve seen the time I’d pass up eighteen dinners just for one beautiful line of poetry. That’s no exaggeration. Eighteen dinners.” He held up all ten of his fingers. “I used to try writing poetry, but then the flare went out of me over about twenty years with a lot of misery in them.”

Daniel squirmed as if screwing himself into the floor. “But it’s not even a beautiful line. It’s obscure. I’m not even sure why it touched me so.”

“Maybe I’ll be able to tell you.”

Daniel looked at him in surprise and grew still. For a moment, neither was conscious of anything but the other, and each for himself did not exist. Daniel forgot why he had come here, that he was facing down likely disappointment. Botto forgot that as a good Christian he hated this sniveling Jew and his humility, his loneliness, all those things to which Botto feared he had or to which he would eventually fall prey. He forgot that he despised Daniel almost as much as he did a glance in the mirror—slightly less so, because at least he could openly admit to disliking the Jew.

Daniel blinked and considered Botto’s boxer’s hand folded before him. The Jew’s expression was never faded, Botto noted, but always expressed some keenness of sense and sorrow, as if seeing the potential for misuse in everything. Yet he had barely enough gumption to protest if Botto were to take him by the neck and begin to squeeze the life out of him. He was the kind that would believe it was God’s will and lift his eyes to heaven instead of bashing him one in return. There was nothing to do for that kind. They asked for it. Botto was almost moved to say, “Learn to fight, you worthless piece of humanity.” He was a welter of emotions. Only the Jew inspired him that way. It occurred to him he should be grateful. He felt increasing disaffection toward those he was duty-bound to love, while toward Daniel, who was nothing to him, he was drawn with undeniable interest, as if because of the opposing desires Daniel inspired in him, to hurt and protect the same individual, he saw himself cast in the roles both of God and the devil and therefore the real type of the great cosmic drama. His other customers he could see taken out and shot in the morning, but Daniel he must have. A discontinuity of emotions was pleasant to him. Perhaps not even three people in a lifetime would spawn such a cursed vortex in his mind. Love was more controversial than hatred, harder to own up to than to hatred. And didn’t the two extremes feed off one another? Botto’s head was spinning. He felt he was being pushed to some decision. If Daniel’s friend didn’t show up soon, he might be compelled to thrash the daylights out of his customer. His hands felt too strong, too capable of violence. His own strength was almost too great a temptation to him.

“Okay, then,” Daniel said in the nick of time. “The line goes, ‘Not even the rain has such small hands.’” He paused. “That’s it. I can’t remember who wrote it or what it comes from, nor even when I bound it. I don’t know anything about it, not what it means, not why it moves me.”

Botto looked at him for a full minute without moving his eyes, and Daniel began picking at a piece of torn plastic covering the menu.

“‘Not even the rain has such small hands,’” Botto echoed after a long while. His voice was ghostly and quiet. Slowly he slid his folded hands toward himself and hid them underneath the table. “You’re right, it is beautiful, but not meaningless, even if we can’t understand it. I think of the rain lightly tapping on the window as ghosts are said to do, or the gentle feel of the mist on the face, so that you could say it caresses you, but more like an angel than a human being.”

Daniel shrugged apologetically. “Who knows? But, needless to say, whenever that line comes back to my mind, I feel I’ve heard again the voice of someone far away. Someone who has seen something, perhaps in a world far different from this one. A world that promises admiration for such a delicate structure as rain-sized hands. They must be very small.”

“As you say, who knows? Poets confuse the hell out of me. But once in a while a line, such as this one, will stop me dead in my tracks. I’ll have to admit, it’s worth the whole lot of them writing night and day for one of them to come up with a line like that. And afterward I’m dissatisfied for a day or so with the rest of the world. But eventually I realize that no matter how beautiful something is, life has to go on and I can’t just dwell on beauty. What a fool I’d be if I did. I have to sober up and remember that this is a world in which people destroy each other, too, and not just in any old way, but with imagination. Yes, poetry is good for maybe one day in twenty. That’s about all the consolation a man can afford himself. You have to be realistic in life. Otherwise you’re asking for it.”

Daniel thought to himself, “He is talking an awful streak. Someone must have hurt his feelings tonight. His kind only becomes friendly when they have to take what they usually dish out. Poor cuss, he’s not half bad, if only someone would hurt him every day. Then maybe he’d tread more lightly on other people’s toes. Tomorrow he’ll rebound. Oh, what a bother it is, not being able to get the same things out of people every day.”

Outside, across the street, stood Nalia Koberg-Franz. The black shadow of the door stoop under which she huddled concealed her. For ten minutes she had been watching the man she recognized as Daniel Buchbinder and another man have a conversation. In fact, she had been hiding there when Daniel passed by and went into the café. These moments of indecision had turned into a life for her. It seemed she was forever twenty feet away from altering her fate and failing to move onward. There didn’t seem to be any overwhelming reason to move out of that doorway and enter the café, except that she had agreed to the date. Why were there no miracles, no voices to say either go or stay? Why was she always on her own, never knowing in any specific instance whether she was her own best friend or worst enemy? At one time she had believed that her life was going to be as well-plotted as a movie, but that illusion was shot and could not be resurrected. There was no one to act for her, and she was too fearful to act on her own.

This Daniel Buchbinder, what was he but some words on paper that had somehow come alive in her mind? It seemed incredible that he was real outside her mind. She was in love, certainly, but that was all under her hat. Her love didn’t need this outside reference. What if she had written all those letters herself? Until she had seen the thin-boned, iron-browed little man sitting there as he promised her he would be, she might have gotten by believing she had made him and the letters up, that he did not exist outside her brain. But now it was too late; she had seen him. What a weak specimen. To think, he had lured her here with such beautiful sentiments and was no beauty himself. Hadn’t he warned her? And hadn’t she written that she wasn’t beautiful either? She had convinced herself she had written that to console him, but come to think of it she had told the truth because there was no denying it. Ah! How could she enter into the harsh lights of the café and know he was thinking to himself, “It’s true! It’s true”?

Didn’t beauty have a strong home these days? It was always found contained in such weaklings. What was that horrible lump in his neck? It kept moving up and down as he talked.

It was cold, but she steamed under her coat. Her ears ached, though, and felt, when she touched them, like they were turning to cheap plastic. She tried to bend one back and forth, but it wouldn’t go. Oh, all this because love was so important! But in another sense she didn’t believe it was necessary. She could put it off a while longer if only she weren’t sweating so under that damned coat.

She had nothing against Jews. She had heard they were just like other people. However, people thought there was only one kind of heavy person. She felt she was it, though she tried hard not to be. That was the way: always worried that she was doing what could cause someone to look at her and say to himself, “Ah-hah! Just like a fat person.” But how could she be true to that self inside her that had nothing to do with size? That self could slip through a keyhole if it wanted. It could be any size, small as a tap on a window someone would look for and not see. Her self was sizeless. She could be words on a page, sentiments expressed. Words, sentiments were sizeless. They could reach into a heart, and no one would know how they got there. They could ache inside a heart, and they were her. She hoped Daniel Buchbinder’s heart ached right now. “That’s me,” she whispered into the cold wind. “That’s me that aches in your little heart with you right now. I’m with you. That’s the size I am. That’s how beautiful I am. Ache! Hurt! Miss me.”

She had nothing against Jews. She had heard they were just like other people. However, people thought there was only one kind of heavy person. She felt she was it, though she tried hard not to be. That was the way: always worried that she was doing what could cause someone to look at her and say to himself, “Ah-hah! Just like a fat person.” But how could she be true to that self inside her that had nothing to do with size? That self could slip through a keyhole if it wanted. It could be any size, small as a tap on a window someone would look for and not see. Her self was sizeless. She could be words on a page, sentiments expressed. Words, sentiments were sizeless. They could reach into a heart, and no one would know how they got there. They could ache inside a heart, and they were her. She hoped Daniel Buchbinder’s heart ached right now. “That’s me,” she whispered into the cold wind. “That’s me that aches in your little heart with you right now. I’m with you. That’s the size I am. That’s how beautiful I am. Ache! Hurt! Miss me.”

Having accepted the fact that for one reason or another he had been stood up, Daniel ordered a bowl of white beans and poured them over crumbled cornbread. On top of this he spread pickle relish and ate, swallowing more than his food sometimes. Nothing went down well when life made no sense. Her most passionate letter had been the most recent one. No doubt she had written her passion out. She had expressed it, and then it didn’t exist anymore. After seven weeks of exchanging letters, her interest peaked and simply vanished. Or perhaps she really did have qualms about dating a Jew. People had their unfathomable reasons. Most of them were personal and outrageous.

Botto was secretly gratified that Daniel’s friend had not shown up, although that sort of treatment a dog shouldn’t have to take. “People, phooey,” was all he could think. “Aren’t they on a lark, all of them? Why should they care about us?” Upstairs Madeleine was probably combing out her hair and thinking of another man, a much younger one, one who said how much he adored her. Botto didn’t blame her for that. Or maybe she was thinking of a much older man, who would soon kick the bucket and leave her fixed to travel. He was certain, anyway, that she wasn’t thinking of him. But he was not pointing the finger. He couldn’t recall the last time he thought of her with anything but impatience and boredom.

“Daniel, old man,” he said from the stove, trying to remember why he had turned on the three extra burners. “So, you thought it best not to wait for your companion.”

Daniel, his head hung over his plate, mumbled, “I can’t wait forever. A man has to eat to live.” He tried to give Botto a look of polite interest.

“Maybe not. Saint Theresa went seven years without food. I don’t know how she did it. But Christ said he was the bread of life, and maybe she had enough faith.”

“That’s a good possibility,” Daniel said.

“None of the rest of us can follow the saints’ examples in such cases. It would be dangerous: they’re an odd lot, exceptions to the rule, every last one of them.”

Daniel was about to say he had lived on hope at least as long as Saint Theresa lived on Christ, but he realized how untrue and possibly disrespectful that was.

Botto went on, “The saints are inspiring, but a little out of our league. Still, we need them in order to understand how short we fall. They lead you to ask what it means to live in the real world. Did they, or do I?”

“What is the use of having an example you can’t follow, just to make you feel bad?” Daniel said, throwing down his fork. “What is the use of having any ideals at all if they are particular and so easily shattered? You can’t go against the grain of life, I’m afraid.”

Botto tossed chicken necks in a pot of boiling water to make broth for tomorrow’s soup and then ladled out the ham hock from the pot of white beans, peeled back a strip of mushy fat, and laid it between two slices of cornbread for a sandwich. He took a bite, and juice spurted out from both corners of his mouth. “After I heard that story,” he said, speaking with his mouth full, “I used to imagine I went to Saint Theresa and tempted her to eat. She ran from me, to hug the cross, and I laughed. But I am not as much of a donkey as I used to be. I don’t think that way anymore. I really stand up for the church. The saints put me to shame, and I don’t laugh at them. I couldn’t tell that story if I hadn’t changed my ways.”

The café door rattled. Daniel turned to see standing on the threshold a woman with glaringly blond hair fixed in sausage curls and, pinned to several of these, a green velvet tam like an inverted bowl, with a battered gray feather standing in it. Bracing her neck was a woolen scarf, which she unwound an incredible number of turns until she had transferred the whole thing to her right forearm and hand like the cast of someone who had been in a terrible accident. Laying her purse down on a bench, she then unbuttoned her coat, but because of the mass around her right arm could only half remove it. She freed her left side, but the coat remained draped over her right shoulder. She picked up her purse and moved toward Daniel, who was frozen to the spot in terror and disbelief.

Judging by her size, this woman had eaten for Saint Theresa those seven years, Botto mused. He paused with his sandwich before his mouth as if he were going to blow a note through it. And so this was it, Daniel had himself a romance going. Every bit of that blond came out of a bottle, but the Jew was too cockeyed in love to know the difference. Daniel himself had no guile and so could not be expected to know when someone was practicing witchcraft on him. What a bitter thing it was to see other people in love, blast them. Botto excused himself to the restroom but watched through a crack in the door. While he was in there, he prayed to Saint Theresa for intercession for a number of venial sins, but not for spying. He cried in self-pity, that he was hopelessly cast for the rest of his days in the role of observer, while this Daniel, who had done nothing much with his life thus far, had the freedom now to rearrange circumstances as he chose. For seven years, Botto had hated the man and all because of the number of possibilities that his aloneness contained. He envied his aloneness because it was the only place from which a new start could be made. And to think, he was forced now to witness the first fruits of all those years of delay. What thanks would he get for letting the Jew peter out his aloneness here?

Daniel was shaking under the table. This was like a nightmare with a lot of light in it. Her not appearing had thrown him back on himself for strength, and he had found some, but now she would depend on him for strength, too, and he realized in a blinding, muting surge of terror what a weak, ineffectual individual he was. Here was no flatness of paper, no leisure of consideration, no access to erasure. This was not like letter-writing at all. What was she thinking? She moved uncertainly to the table, avoiding his eyes, and sat down opposite him, staring pensively at the table. The words, “Give me back ....” shot through his mind, but he could not finish them. He lifted his toes against his shoes and felt the nails pressing into his flesh.

She was much prettier than he had imagined she would be, but her cheeks sagged and the skin under her eyes had darkened as if she were exhausted after a long trip. Her mouth was small, and the upper lip came to two distinct peaks. It was painted in vividly-red and wet-looking lipstick. As for her shape, she was a plum, a bit hefty, but weren’t all ripe things? He couldn’t imagine agreeing with her on any score. She was totally the opposite to him, from her sex on down. Perhaps for the first time he understood the old saying, “opposites attract.”

Finally he worked up the courage to say, “Nalia Koberg-Franz?”

When she first came in, her face was a bright pink from the cold, but by now it had turned stark white.

She nodded but still did not meet his gaze. This was dreadful for both of them. First meetings were barbaric. He wanted to mention how horrible this was for both of them, that nothing on the face of the earth could make it a graceful situation. But after all, hadn’t he heard that the way to treat a bruise was to apply pressure to it? And how awful to meet someone who was as lonely as you, lonely to the extent of writing letters to a stranger, but to be unable to mention that because of the taboo. Weren’t they both ashamed of the terrible thing that had driven them together? How would they ever be able to face it?

Suddenly she looked him directly in the eye. “Daniel Buchbinder?”

“Yes,” he answered.

“Good evening.” She nodded coldly.

“Good evening.”

She lifted her large black purse from the floor and rummaged in it long enough without producing anything that he wondered if she did so merely for comfort. At last she pulled out a letter-size manila envelope that must have been evident all along, but which she greeted with an expression of combined surprise and relief. She held the envelope in both hands and examined his face with curiosity. “Buchbinder,” she said. “Deutsch for bookbinder. Coincidence or not you are bookbinder and Buchbinder?”

Daniel tugged at his knees.

She went on. “My name is a place to which I have never been and which cannot describe me concretely. But your name names a profession which does describe you. How is that? Just curiosity. Did you take the name because of the profession, or the profession because of the name?”

Nalia removed her tam, and one of her curls shot out like a spring wound taut and released.

He nodded. “Oh, feel free to wonder. Wonder and ask.” He laughed and swaggered his torso in a manner that he feared gave the impression of feeblemindedness. He was so uncomfortable, he was ready to burst into tears when all of a sudden he thought of something intelligent to say: “Yes. If your name were to you as mine is to me, you would be called ‘Nalia Schoolteacher.’”

She cocked her head and flared her nostrils in distaste. “Keep that little bit of information to yourself. I hate my profession and always have. The problem is, I like things to be perfect, and they never are when you’re dealing with young American minds. I need a free hand to discipline, but I notice you can’t even get that in prison anymore.”

“No,” he said, “I am the fourth generation in this country. My great grandfather immigrated in 1902 with both the name and the profession. But I imagine the link occurred several generations prior to that. Once artisans took for surnames the names of their trades. But now with people changing jobs every time their backs ache, naturally it’s not as much of a practice.”

She lowered her head and looked up at him as if shyly seeking faith. “And you do good work?”

“At the risk of tooting my own horn: the best that can be had.” He thought of his earlier conversation with Botto, and his spirits drooped. “But it doesn’t matter. We all die, and books go unread. People work hard enough without having to sit down and figure out what all those characters mean.”

“But it matters to me.” She opened the envelope and withdrew a small bunch of papers. “You see, I have something I want bound, a group of letters from a friend, purely of sentimental value, not literary, not monetary.”

“My favorite kind of work to be preserved. Has a chance of being looked at again, eh?”

“They were folded,” she said, laying the pieces of paper on the table between them and placing her hands on top of them. “I ironed them. To try to flatten them out. I’ve done very well.”

He took the pages from her. “Will be a thin volume, Nalia Koberg-Franz.”

“Macht nichts, Daniel Buchbinder. Those letters are full of individual lines that would move mountains. Listen!” She touched his hand, and he felt the tiniest involuntary surge of bliss reach his heart. He was sure he had a heart: that fact, which once had been the source of much unhappiness, now seemed to turn its other cheek toward him and reveal a different face entirely.

She quoted a line he recognized as one he had slaved about two hours to write and finally stolen from various sources: “‘In time to come, I will honor you with my entire being, I trust, and this honor will be great enough to form worlds, though body and soul I were no larger than a raindrop.’”

Daniel slumped down slightly in his chair and hoped Botto could not hear their conversation from the men’s. “Such schlock as this,” he said, his face turning the color Nalia’s had been when she first entered.

“Schlock, maybe,” she said, leaning toward him and smiling strangely, a fleck of boldness in her eyes, “but I wouldn’t trust anyone but you to bind it.”

A woman that size, and away she went without ordering a bite! He saw twenty, twenty-five dollars go out the door. Hadn’t she looked starved? Disgruntled, Botto emerged from the bathroom and picked off Daniel’s table the money he had left for his meal. Those two had departed quickly. There was some talk of business, but he couldn’t hear how it went. And just when he was thinking to himself, “Oh, he’s only meeting a potential customer,” he saw them link arms as they passed the front window. “Come back to the shop, I’ll show you the procedures,” he’d heard Daniel, the lady-killer, say to her.

Botto sat down on a revolving stool at the counter and tried to satisfy himself by recalling his first meeting with Madeleine, but at the same time he happened to glance up and meet his reflection coming to him out of the mirror. “You old wreck,” he muttered. Why had he been born with one ear half the size of the other, as though that smaller ear were for listening to things from his youth? Well, he was practically deaf in that ear, if anyone cared to know. Look for the memory of a first meeting in that bloated gristly-nosed face? It was like looking for a particular drop of water in a rusty bucket. All the life that had flowed from his love for Madeleine couldn’t have happened, for what woman would look twice at that jug? He laid his head in the crook of his arm and wept again, as if Daniel had stolen his romance. “To be assured of nothing in life,” he moaned, “and yet to have what seems like everything taken away from you. How terrible!”

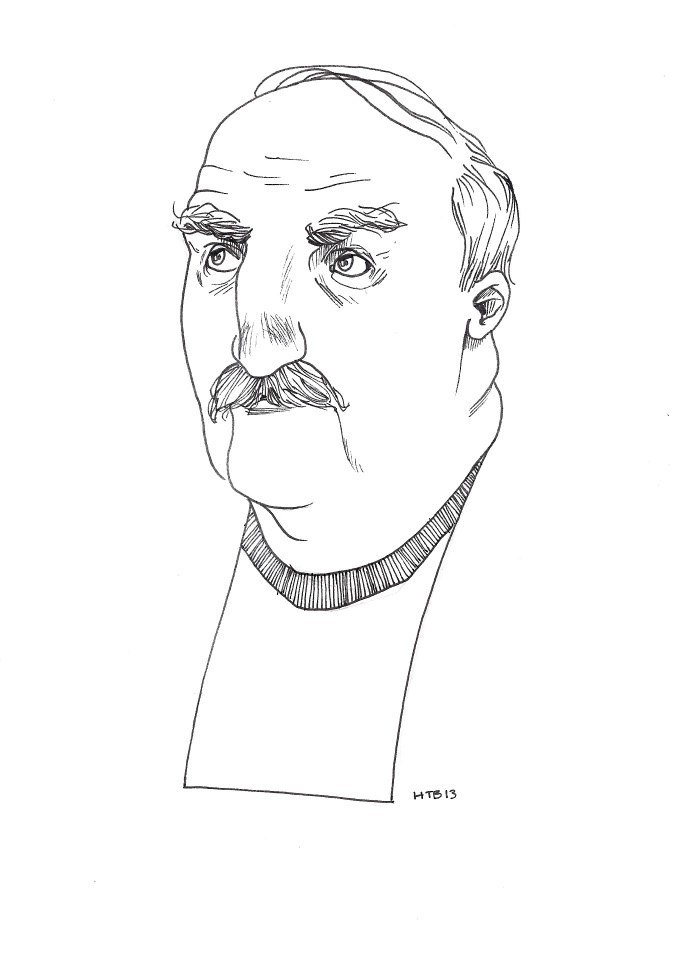

David Vardeman is a native of Iowa and a graduate of Indiana University Southeast and the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His one-act plays have been staged by New England Academy of Theatre, Bellarmine College, Acorn Theatre’s Maine Playwrights’ Festival, Mad Lab Theatre in Columbus, Ohio, and the Theater Company of Lafayette, Colorado. His full-length play Because It is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart was one of six finalists at the Palm Springs International Playwriting Festival in 2004 and received a staged reading. His short fiction has appeared in Crack the Spine, Glint Literary Journal, Life As An [insert label here], and Little Patuxent Review and is forthcoming in The Writing Disorder. He lives in Portland, Maine.

Harriet "Happy" Burbeckis a New Orleans comic artist, illustrator, and musician. She has shown her work at a number of galleries in the Crescent City, including Mimi’s in the Marigny, Du Mois Gallery, Zeitgeist Multi-Disciplinary Arts Center, and The Candle Factory.