Our second issue will be out in October, and although we won’t be releasing any previews of contributed work this time around, I’m posting the text of my editor’s note here. What do you think the purpose of art is or should be? You can comment on this post and tell us what you think.

Editor’s Note (PDR Vol. 1, Issue 2)

Kills Bugs Dead. This is probably the best slogan I have ever read. On its own, the phrase “kills bugs” is purely descriptive. It’s obvious and eminently forgettable. But that extra word at the end—its redundant, reassuring finality—that’s what let’s you know: with this insecticide there will be no half-measures. It is Ragnaroach; it is the bugpocalypse.

I’m told that the tagline was penned by Beat Generation poet Lew Welch while he was doing a stint as an adman in New York. The phrase is artful and effective, but is it poetry? Whatever our disagreements about the purpose of poetry in our culture, I think we can agree that selling pesticides is ancillary to that, something tacked on after the fact. Advertising is an activity that makes use of poetry for some purpose not intrinsic to the literary form.

On the other hand, defining art and its purpose is a risky business. It leads so easily to aesthetic prescriptions that stifle experimentation and condemn original work to either obscurity or derision. History shows us that, in authoritarian regimes at least, failure to adhere to the proper style of art-making can have grim consequences indeed. Still, shouldn’t we be able to say something about what art is for and what is foreign to it?

We can look to ethics, already concerned with how things ought to be, for help thinking through the question of the proper approach to art. In his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, the philosopher Immanuel Kant suggests the following bedrock ethical principal:

Now I say that the human being … exists as an end in itself, not merely as a means to be used by this or that will at its discretion; instead he must in all his actions, whether directed to himself or to other rational beings, always be regarded at the same time as an end.

Kant argues that we must treat every person we meet as an autonomous being, a consciousness with the capacity to think for itself, set its own goals, and make its own choices.

If I disregard the interests of another person and exploit her solely as a means to some purpose I have in mind (personal profit, say, or sexual gratification), then I have a distorted relationship to that person.

We don’t have to agree on the precise purposes of art in order to adopt the principle that works of art, like individual human beings, exist as ends in themselves. If we grant that art has its own ends, independent from other dimensions of society (the economy, the state, etc.), then it follows that these ends should be respected.

In practical terms, this means affirming a difference between art that has been allowed the freedom to pursue its own ends and art that has been subordinated to some other purpose entirely. When art is used only to achieve some end external to it, when its autonomy is denied or disregarded, art is inevitably degraded. I’m not arguing for some fantasy of purity—art may pursue its own ends and still manage to sell something or support a political cause in the process. I believe, however, that we should be mindful that the primary purpose of art is probably not to produce profit for commercial publishing houses, to stimulate desire for commodities, or to advocate for a political ideology.

It is the purpose of this magazine to support art on its own terms. Some might even say we take this position to an extreme. Printer’s Devil Review refuses, for example, to subordinate art to the market and turn it into a commodity. We give the journal away for free and license the content in such a way as to facilitate its unrestricted circulation.

I’m starting to think that we’ve been asking the wrong questions, or at least in the wrong order. What if we asked not “what is the proper function of art?” but rather “what does art want”? How about this for a slogan: Art Wants to Be Free.

Thomas Dodson

The Fall 2011 issue of Printer’s Devil Review is here and

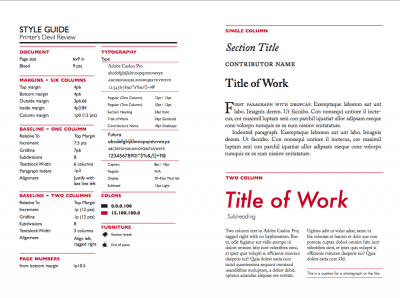

The Fall 2011 issue of Printer’s Devil Review is here and  As my section editors have been working on selecting and editing new work for our second issue, I’ve been re-working the look and feel of the magazine.

As my section editors have been working on selecting and editing new work for our second issue, I’ve been re-working the look and feel of the magazine.  Lush, brooding landscapes of curlicues, spiderwebs, insects, and fruit, all digitally designed and painstakingly cut–this is the world of

Lush, brooding landscapes of curlicues, spiderwebs, insects, and fruit, all digitally designed and painstakingly cut–this is the world of  We normally shy away from genre fiction, but The Dying Nude, a novel-in-progress by Allan Converse, is something special.

We normally shy away from genre fiction, but The Dying Nude, a novel-in-progress by Allan Converse, is something special. A few months back, the

A few months back, the